9.3

8.251 reviews

English

EN

This article has been automatically translated from Dutch. Click here to see the orginal article including all links to sources.

The ECB is keeping interest rates unchanged for now, but tensions are building beneath the surface. In this weekly selection, we examine why, according to some economists, the European Central Bank will ultimately be forced to intervene to weaken the euro and generate inflation. And why the so-called debasement trade may be better described as a debasement trend.

The European Central Bank (ECB) announced this week that it would leave interest rates unchanged. The deposit rate therefore remains at 2 percent. Inflation in the euro area declined from 2 percent in December to 1.7 percent in January, mainly due to lower energy prices. This places inflation below the ECB’s 2 percent target, yet according to ECB President Christine Lagarde, monetary policy is nevertheless “in a good place.”

Christine Lagarde (source: European Central Bank)

In the Netherlands, inflation fell from 2.8 percent in December to 2.4 percent in January, a level that remains clearly above the eurozone average.

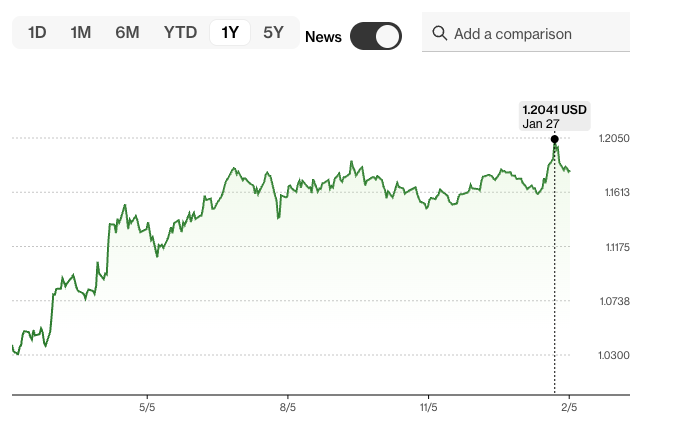

Last week, we wrote about the appreciation of the euro against the dollar. A relatively strong euro can have a negative impact on the eurozone economy, as European products become more expensive for American consumers, while U.S. products become cheaper within the EU. This weakens the competitiveness of European companies and, through lower import prices, can also put downward pressure on inflation.

This explains why Lagarde stated in her speech that a stronger euro could cause inflation to fall further than currently expected. As we have written before, central banks aim for inflation rather than deflation due to debt sustainability concerns. Inflation reduces the real value of debt, while deflation increases it..png)

The ECB intervenes when the euro becomes too strong against the dollar (source: Bloomberg)

In her remarks, Lagarde downplayed the impact of the recent euro rally. She stated that the ECB does not target exchange rates, but does take their influence on inflation and economic growth into account. In practice, however, we have seen in the past that the ECB has intervened whenever the euro rose above $1.20. This week, the exchange rate briefly moved above $1.20 again before falling back. If the rate were to rise further beyond that threshold, policymakers are expected to take it into consideration.

EUR–USD exchange rate, 6 February (source: Bloomberg)

France is already increasing the pressure. President Macron wants to put the appreciation of the euro against the dollar on the agenda at an EU summit on European competitiveness and economic stimulation. France not only benefits from a weaker euro due to exports, but could also use a loosening of ECB policy for another reason. Inflation in France is very low, while the country’s debt burden is very high, and there appears to be no political way out.

Interest expenses could explode (source: Financial Times)

France is not alone. Across large parts of the developed world, government debt and interest expenses are rising. We previously discussed the situation in Japan and the United States. Governments are running structural budget deficits and financing them with debt. Jeroen Blokland argues that this situation is simply unsustainable and that central banks will ultimately be forced to monetize these debts.

Debt monetization through money creation inevitably leads to inflation, reducing the real value of the debt burden. The alternative is a full-blown confidence crisis in the financial system. According to Jeroen, the choice will ultimately fall in favor of higher inflation: “I don’t know when the Bank of Japan will capitulate. I do know that at some point it will have to.”

According to Jeroen, Kevin Warsh—the intended successor to current Fed Chairman Powell—will ultimately face the same choice, as interest expenses are set to rise sharply in the coming years. Many media outlets suggested that Warsh would pursue a stricter policy, which is why prices of several precious metals fell last week after the announcement that he would replace Powell. According to Blokland, this reaction is unjustified, as Warsh is also likely to opt for further debasement.

Robin Brooks wrote this week that the market is already pricing in further rate cuts and no longer expects tight monetary policy. He anticipates that Warsh will cut rates quickly, even before the midterm elections in November. That was also an important selection criterion for Trump when appointing a new Fed chairman. According to Brooks, the arguments for further dollar weakness are continuing to pile up.

Brooks expects the dollar to weaken further and believes that the gold price will rise again in the foreseeable future. According to him, the flight to safe havens will continue, as nothing has fundamentally changed in the unsustainable debt and fiscal policies.

Further dollar depreciation increases the pressure on the ECB to prevent the euro from becoming too strong and damaging competitiveness. Even without this, that pressure already exists due to the debt sustainability of countries such as France and Italy. Fiat currencies appear to be engaged in a race to the bottom. The only direction seems to be downward. The term debasement trade may no longer fully capture this development. The erosion of purchasing power appears more structural in nature, making debasement trend a more accurate description.