9.4

7.516 Reviews

English

EN

In the Previous piece On monetary history, we described how the Dutch fought their way away from the Spaniards and how the expensive wars against the Spanish and the English were financed. However, there is much more to tell about the Golden Age, including the use of money by the Dutch. What kind of money was used in the Republic and what role did the guilder play?

Great variety

As we have also described in the previous article, the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands was still very decentralized compared to the current Netherlands. The provinces went to war together against the Spaniards and the costs of the war were divided, the so-called quotas. For the rest, the provinces were still very independent and there were also cities within the provinces that had their own privileges and wanted to make their own decisions.

If a city had city rights, it also acquired the right to mint coins itself, just as provinces were allowed to mint their own coins. Be an interesting exampleGroningen coins. Until 1593, Groningen had a very special position in terms of coins in the Dutch Republic. The basic coin was the silver penny which was divided into six slices, but the Groningen penny was worth slightly less than nickels from other provinces. It was not until 1593 that the system was amended and a new system was introduced, modelled on other currencies in the Republic.

For example, many regions had their own currency in circulation. For a long time, there was no single uniform currency in the Republic, which only came into being in the twentieth century. In certain regions, there was also still a lot of foreign money in circulation, for example from German areas. Finally, people also paid with coins from earlier eras, such as the silver Philipsdaalder and the Carolus guilder which appeared in both silver and gold. These coins were introduced during the Spanish reign.

As a result, coinage in the Netherlands was very fragmented and a jumble of coins had arisen. The circulating coins varied from rijksdaalders to ducats and from florins to Groningen stuivers. In the early days of the Republic, it is estimated that there were more than 500 gold and 340 silver coins in circulation, according to the book From Gold to Bitcoin!. All these coins were then converted into certain units of account. So the system was quite cumbersome and confusing.

A golden rider, minted in Utrecht. This was one of the most valuable coins in the Republic. (Source; Wikipedia)

Money changers and cashiers

The sheer variety of coins also required a craft that could set off different coins against each other. Money changers were therefore widely present in the early days of the Republic. Wealthy merchants used cashiers to make their payments and collect their bills. These cashiers also specialized in the vast amount of coins that were in circulation.

These money changers had to weigh coins over and over again. In addition to high-quality money, there was also low-quality money in circulation. So pruned coins are coted by grinding metal off the edge. Issuers also minted lighter coins, which reduced the intrinsic value of the coin. However, this did not affect the issuer, as the face value of the coin was fixed in a placard which was issued by the States General. Because coins were stamped and thus allowed, the face value was up to 15% above the intrinsic value.

The money changers started writing more and more notes to arrange these payments. This ensured that their promissory notes and cashier's receipts could also fulfill the function of money again, as can be read in the book A financial History of the Netherlands. So, in principle, the notes functioned as money, but they differed from the fiduciary bills issued by the central bank today.

Exchange bank

It was noticed that the fragmentation of the coinage shook confidence and was extremely difficult for the payment system. Money changers also askedFees for their services. In order to put the payment system back in order, the Amsterdam Exchange Bank was founded in 1609 with the support of the Amsterdam city council. The Exchange Bank checked coins that were deposited with the bank and so account holders knew that they would also receive high-quality money back. In this way, the bank guarded the integrity of the money.

A second advantage of the Exchange Bank was that it created a platform for cashless settlement. Merchants who held an account could easily make transactions among themselves via the Amsterdam Exchange Bank and no longer needed the cashiers for all transactions. Many merchants were forced to maintain an account with the bank, as the city council demanded that all transactions from 600 guilders through the Exchange Bank.

The bank thus took over a large part of the money changers. Money changers and cashiers were even banned in Amsterdam for a short time, which further strengthened the position of the Exchange Bank. From 1621 they were allowed again, on the condition that they also kept an account with the Exchange Bank and did not carry coins for more than 24 hours.

Initially, the Wisselbank was located in the old town hall in Amsterdam. After the building burned down in 1652, the Exchange Bank moved to Dam Square. (Source; Wikipedia)

From 1683 onwards, the Exchange Bank also issued a kind of paper money, a Recepis. This was a receipt for precious metals or coins that had been deposited with the bank and would be returned after a certain period of time. This paper could also be used to make payments. If the holder of the recepis needed money, the recepis could also be sold on the Amsterdam stock exchange. Ironically, the trade in these receipts was controlled in part by cashiers.

These recepises ensured that it was not necessary to withdraw physical coins from the Exchange Bank. After all, the account holder could sell the receipt on the stock exchange. As a result, the bank guilder was in effect Disconnected of the money outside the bank. The Exchange Bank was also able to conduct monetary policy by issuing recepises. As a result, the money supply changed and the Exchange Bank took a position that is now assigned to central banks.

The Amsterdam Exchange Bank was so successful that other cities set up a similar bank. Middelburg, for example, followed Amsterdam's example in 1616. Later, people could also deposit money at the Delft and Rotterdamse Wisselbank. Nevertheless, the Amsterdam Exchange Bank remained by far the most important. The number of account holders was also much larger than that of other banks, including those abroad.

End of Exchange Bank

People could not borrow money from the Amsterdam Exchange Bank, so they had to go to the Banks of Leening. However, the Wisselbank did lend money to the VOC and the Amsterdam city council. Regularly, there was not enough cash available to cover all deposits. Coverage was still hovering around 90 percent in 1683, but later declined.

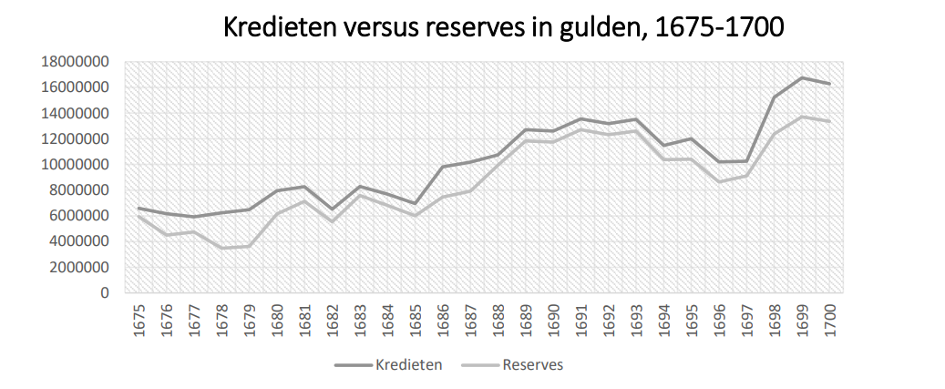

The amount of cash and loans that the Exchange Bank had outstanding. (Source; Vriendenvandewitt.nl)

In the eighteenth century, the bank began to grant more and more risky loans, without publicity. When it came out in 1794 that the Wisselbank had secretly provided loans to the VOC, which was in great difficulty at the time, unrest arose. In addition, it turned out that money had been lent to the board of Amsterdam. This was the beginning of the fall of the bank. People who trusted that their money was safely stored in the vaults of the Exchange Bank were disappointed. In 1820 the Amsterdam Exchange Bank closed its doors. Much of the gold was already gone by then.

The story about the fall of the Amsterdam Exchange Bank is reminiscent of the story of the crypto exchange FTX. FTX had lent about $10 billion in customer deposits to its affiliated company Alameda Research. In November, there was unrest after it came out that there were holes in Alameda Research's balance sheet and Binance announced that it was going to sell the FTT tokens, tokens that were issued by FTX. Many people started withdrawing money from the exchange, but FTX turned out not to be liquid enough to pay out customer deposits, just as the Amsterdam Exchange Bank was no longer when French troops invaded the Republic.

It is interesting to see how finance developed in the Low Countries. The wide variety of coins called for the establishment of the Exchange Bank, which made Amsterdam the financial center of the world. At that time, the first shares were issued in Amsterdam and a trade in derivatives was created. In 1672, the struggle against the French, Germans and English brought an end to the Golden Age of the Republic, but we still owe a large part of our wealth to this period. In the next piece, we describe what happened to the Republic.

![]() Have a look at us YouTube channel

Have a look at us YouTube channel

On behalf of Holland Gold, Paul Buitink and Joris Beemsterboer interview various economists and experts in the field of macroeconomics. The aim of the podcast is to provide the viewer with a better picture and guidance in an increasingly rapidly changing macroeconomic and monetary landscape. Click here to subscribe.