9.4

7.516 Reviews

English

EN

In the Previous piece In the series on monetary history, we described what the monetary system in the Republic looked like at the time of the Golden Age. For example, it was described how more than 800 coins were accepted in the Republic and how this led to the establishment of Exchange Banks, such as the one in Amsterdam. But what happened next? How did the Republic develop after the disaster year and how did the monetary system change?

New era

It Disaster year 1672 is often seen as a turning point for the power of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The Netherlands were attacked by France, England and German bishoprics. It was the end of the Golden Age and in the years that followed, the Republic was no longer seen as a world power. Wars had accumulated sky-high debts. In the eighteenth century, more debts were contracted, as a result of which the national debt had risen to five times the national income. As a result, the trust that the Republic enjoyed in the seventeenth century had greatly diminished in the eighteenth century, as can be read in the book A Financial History of the Netherlands.

In 1672, about one-third of the annual budget was allocated to pay the cost of debt. The rest of the budget went largely to the military. In the years after 1720, due to higher debts that the Republic had accumulated, only a third of the budget remained for the war effort. The armies that the Republic needed could no longer be maintained.

As a result, the Netherlands was no longer a world power. Not only did the trade networks of the Republic come under pressure, but also the national borders could no longer be defended. At the end of the eighteenth century, the Republic was overrun by French soldiers.

Establishment of the Dutch Central Bank

As early as 1772, during a crisis on the Amsterdam stock exchange, an idea arose to form a private fund that would provide funds in times of liquidity shortages. However, this plan did not get off the ground successfully for a long time. It was not until William I was appointed King in 1814 that the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) was founded. The commissionfor the new institute read; 'to lift commerce, as the nerve of this state, from the decay into which previous times and circumstances have brought it'.

Initially, the Dutch Central Bank had a fairly limited range of tasks. For example, the bank was allowed to provide credit to traders against collateral. The bank was also allowed to trade in gold and silver. However, DNB was not allowed to accept deposits from companies or individuals. Only the state was allowed to hold deposits with the bank.

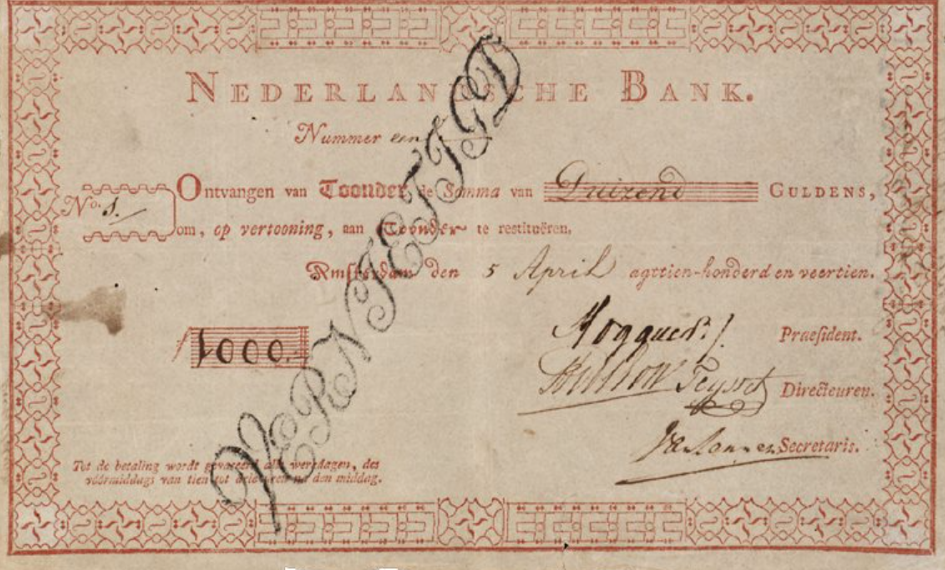

DNB also became the first institution to start issuing banknotes, although there was no monopoly on the issuance of banknotes at the time. The notes were printed in denominations of 25, 40, 60, 80, 100, 200, 300, 500 and 1000 guilders and were printed on only one side. That is why the first banknotes wereRobins said. Until 1825, the president of DNB still personally signed all banknotes. Only later was the signature printed on the banknote, says economist Edin Mujagic in his Lectures.

A banknote from DNB's first series. For the delivery of the first 20,000 banknotes, 542 guilders were paid. (Source; De Nederlandsche Bank)

The banknotes were not widely used. This is because the average worker earned between 30 and 40 guilders per month and the note with the lowest denomination was 25 guilders. The notes were therefore not suitable for everyday payments. At the time, people were also still very suspicious of paper money, partly because of the fiasco with French assignats. These assignats were introduced in France in 1716 and then rapidly declined in value because they were issued almost indefinitely.

So people were very suspicious of paper money. Cashier's receipts were the exception to this. These were payment orders that people could submit to their cashier. Cashiers originally managed client assets for a fee, later they also began to provide loans against collateral, albeit to a limited extent. In practice, the cashier's receipts functioned as local City tickets. Especially if the cashier was reputable, cashiers paper went from hand to hand.

Help from an unexpected source

The Dutch Central Bank had a very difficult time in the early years. This is also evident from the first share issue. The first 5000 shares issued by DNB were not very popular with the public. A number of bankers were found willing to buy more than one and a half million guilders' worth of shares. In addition, the royal family invested 400,000 guilders and the state also contributed one million guilders, but this was not enough to get DNB off the ground.

Help eventually came from an unexpected source. At the time, cashiers were not happy with the arrival of the Dutch Central Bank. The institute was able to drive the cashiers out of circulation by taking over the duties of the cashiers. Nevertheless, the last capital was provided by Widow Johanna Borski, which was affiliated with cashier's company Cassa. In 1814 the widow gained control of the large fortune of her husband, Willem Borski, one of the Founders of the Cassa Association. The last 2,000 shares needed to establish DNB are bought by Borski.

This is subject to the condition that DNB does not issue any new shares in the following three years. In principle, the widow does not benefit from the establishment of the bank, but she does see an opportunity to make a lot of money with the shares. Shares rise sharply in the following years, as people gain more confidence in the bank. The widow died in 1846 as the richest woman in the Netherlands with a fortune of four million guilders.

Johanna Borski, who made the establishment of the Dutch Central Bank possible. (Source; Amsterdam Canal Houses)

DNB expands

Although DNB had a limited range of tasks when it was founded, the Dutch Central Bank expanded from 1938 onwards. In addition to the state, from that moment on ,Individuals Open an account with the bank. In addition, a commission of only half a percent was levied, relatively lower than the commissions charged by cashiers. This angered the cashiers, who feared that the low commission charged by DNB would set the scythe in their activities.

At that time, an important part of the payment system was in the hands of cashiers. In the early days of the Dutch Central Bank, cashiers had relatively little to fear from the banknotes issued by DNB, but over time the DNB banknotes enjoyed more trust and acceptance. When DNB expanded further, this was met with resistance from the cashiers.

The aforementioned Cassa Association went Issue your own bearer paper to counterbalance DNB. Through the Haarlem printing company Joh. Enschedé & Zoonen, which also printed the banknotes for the Dutch Central Bank, banknotes came into circulation in denominations of 100, 500 and 1,000 guilders. Although cashiers' paper circulated mostly locally, these notes were intended for use on a larger scale. With the introduction of the new banknotes, an attempt was made to drive DNB's banknotes out of circulation. This was permitted because DNB did not yet have the exclusive right to issue at that time.

In response, DNB decided to exchange the new banknotes free of charge for paper issued by the Dutch Central Bank. DNB had the advantage that it was exempt from stamp duty, while Cassa's banknotes had to be stamped. The solution to this conflict consisted of Cassa's promise to stop issuing banknotes and DNB's promise to no longer exchange the cashiers' banknotes free of charge, according to the book De Nederlandsche Bank by Wim Vanthoor.

Issuance criteria

With the fiasco of the French assignats still fresh in their minds, the Dutch Central Bank had to find a way to establish confidence in the banknotes. The bank did this by limiting the number of notes that were issued and by holding enough precious metal. At that time, bills could still be exchanged for gold.

Wim Vantoor's book also describes exactly what was going on with the coverage of paper money. From 1847 onwards, there was a maximum for the amount that could be spent on bills. There will also be rules for the coverage of the issued bills. In 1847, for example, 52 million guilders worth of banknotes were allowed to be issued, 40 percent of which had to be backed by precious metals.

This provision was amended in the years after 1847. In 1857, for example, there was a maximum amount of 150 million guilders in banknotes and the first 100 million had to be 40 percent backed by precious metals. If DNB wanted to issue more than 100 million guilders worth of banknotes, those extra banknotes had to be fully backed by precious metals. This is how the term 'available metal balance' appeared. This was the difference between the available stock of precious metal and the value of the issued banknotes. On the basis of that balance and the maximum stipulated, it was determined how many banknotes DNB was allowed to put into circulation.

This is how the Dutch Central Bank was founded. Although DNB struggled to get off the ground in 1814, DNB's paper money gradually became accepted as a means of payment. In this way, the Dutch Central Bank established more confidence and was able to play a greater role in the Dutch economy. In the next section, we will take a closer look at the role that DNB would play.

![]() Have a look at us YouTube channel

Have a look at us YouTube channel

On behalf of Holland Gold, Paul Buitink and Joris Beemsterboer interview various economists and experts in the field of macroeconomics. The aim of the podcast is to provide the viewer with a better picture and guidance in an increasingly rapidly changing macroeconomic and monetary landscape. Click here to subscribe.