9.3

8.058 reviews

English

EN

This article has been automatically translated from Dutch. Click here to see the orginal article including all links to sources.

This past Monday, the gold price broke through the €105,000 per kilo mark for the first time ever. In September alone, the price rose by about 12 percent. That’s an impressive return—well above the average annual gain of 9.5% in euros over the past 25 years. But this time, that level of return was achieved in just one month. So what’s behind this massive surge in September?

There has been plenty of online speculation about the causes of the recent gold rally, but economist Robin Brooks insists there is only one true driver. And before gold holders get too excited: Brooks calls this development “highly revealing and deeply troubling.”

According to him, the decisive factor is not central banks buying gold to reduce their dependence on the dollar, nor a broader market exodus from the dollar due to chaotic Trump-era policies.

While these forces were decisive in earlier cycles, Brooks argues that the only explanation consistent with recent market movements is the global rise in government debt. The growing unease in markets, he says, stems from expectations that this will inevitably lead to higher inflation.

He sees investors fleeing from all ten major currencies and writes: “It seems that markets are increasingly worried about a broad erosion of all G10 currencies, not just the U.S. dollar. That explains why gold has surged so strongly since Chair Powell’s softer Jackson Hole speech, while the dollar remained stable against the G10.”

Since Powell’s speech on August 22—effectively giving the green light for further Fed easing—gold has surged by 16 percent against the dollar. In the 4.5 months prior, the market was in consolidation, with prices virtually unchanged. The orange line in the chart shows the dollar holding steady against G10 peers since Jackson Hole, while gold (the white line) shot up.

For Brooks, this shows the rally is not a flight from the dollar, but from all G10 currencies. It is a flight out of fear of debasement. He points to the rise in long-term government bond yields as further confirmation of this theory. Gold is now cementing its role as the ultimate safe haven.

In a recent podcast with Jeroen Blokland, we already discussed how central banks will ultimately always come to the rescue of governments with heavy debt loads—by fueling inflation and cutting rates. Were there other signs this week that reinforce Brooks’ thesis?

According to CNBC, the “big trade” among retail investors right now is the so-called “debasement trade”—a bet on currency devaluation. Analysts at JPMorgan note this trend particularly among retail investors, who are increasingly worried about swelling budget deficits, the Fed’s independence, long-term inflation uncertainty, and eroding trust in fiat money.

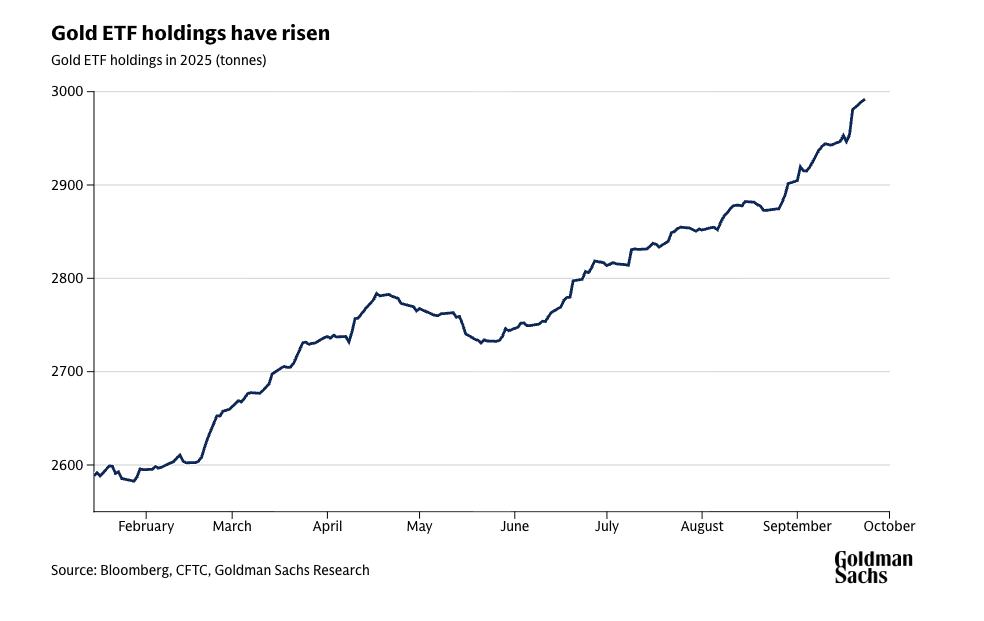

As a result, more and more investors are seeking refuge in bitcoin and gold. This is reflected in the sharp inflows into gold ETFs—again aligning with Brooks’ thesis.

While fears about inflation are mainly long-term, this week’s new inflation readings also reinforced those concerns. Global money supply has expanded at an annualized pace of 7.5 percent over the past six months.

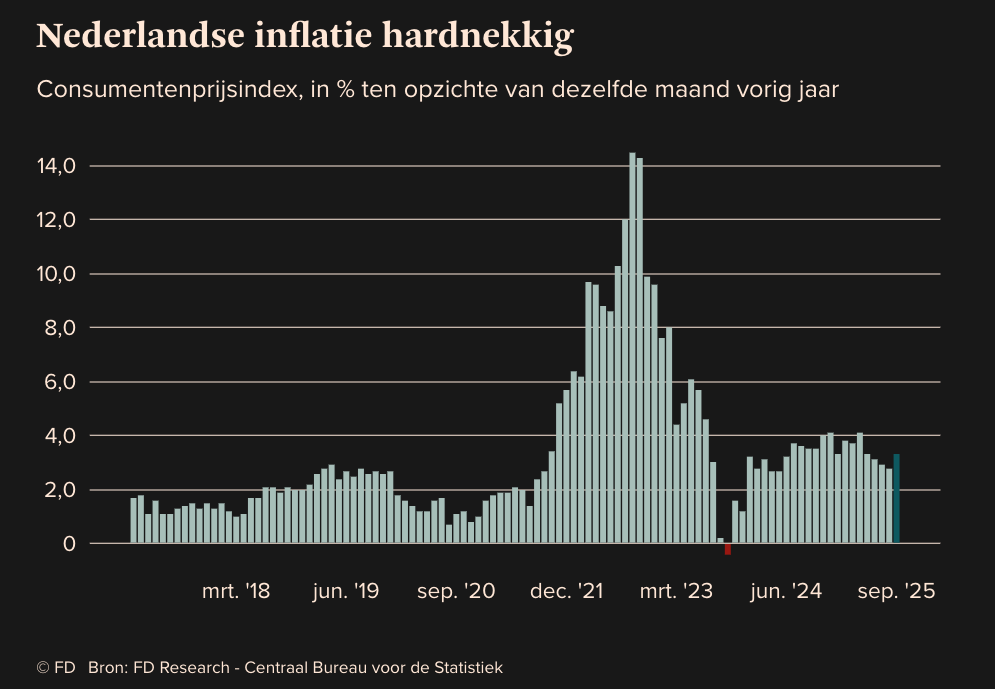

In the Netherlands, year-on-year inflation in September came in at 3.3 percent, breaking the downward trend in place since April. That was higher than analysts expected—and far above the interest on an average Dutch savings account.

In Germany—where the government recently scrapped its debt brake—September inflation also rose faster than expected, hitting 2.4 percent. Eurozone inflation as a whole climbed to 2.2 percent, a five-month high. The conclusion everywhere is the same: price pressures remain sticky.

Within the euro area, Estonia recorded the highest inflation at 5.2%, followed by Croatia and Slovakia at 4.6% each. The cumulative effect of recent years is significant: according to ECB and Eurostat data, Dutch food prices have risen nearly 40 percent since the end of 2019.

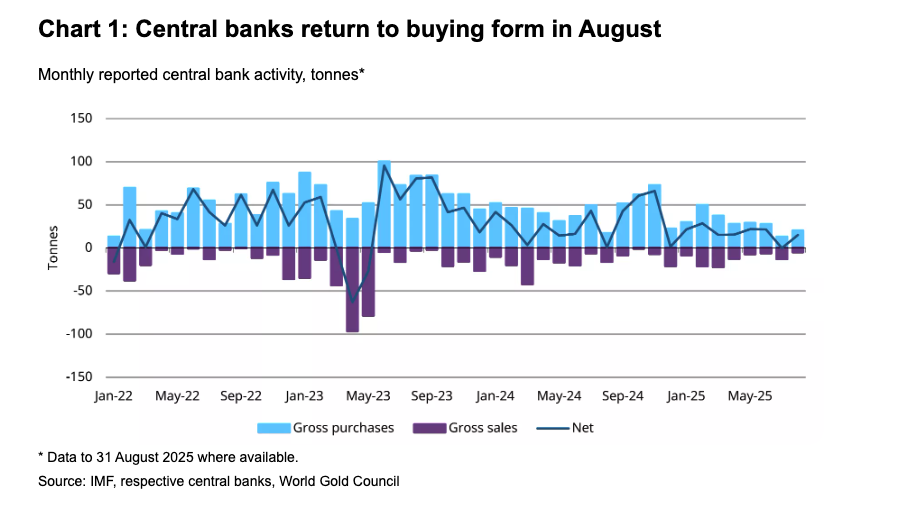

In recent months, central bank gold purchases slowed somewhat. In July, global reserves remained unchanged. According to the World Gold Council, record-high prices likely restrained buying activity.

But this does not mean central banks are losing interest. On the contrary: in August, they added a net 15 tonnes to their reserves, roughly back to levels seen earlier this year.

The numbers for September are not yet in, but based on current data Brooks’ theory holds up: central banks did not buy more than usual in August. Unless their purchases turn out to have surged in September, it is likely that the bulk of the recent rally stems from other causes.

Goldman Sachs, meanwhile, expects central banks to continue accumulating gold over the next three years—meaning they will remain a powerful force in the gold market.