9.3

8.064 reviews

English

EN

In the Previous piece The series on monetary history described the banking crisis in the period after the First World War. Several banks ran into problems due to overly lenient lending and the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) had to take firm action, as a result of which it increasingly became the central bank of the country. But what happened during the interwar period? The gold standard was reinstated after the First World War, but was nevertheless soon abandoned. Why did countries abandon the gold standard fairly soon after its introduction?

We saw In a previous piece that many countries abandoned the Gold Standard during the First World War, in order to finance the very expensive war. In the 1920s, many countries were looking for ways to strengthen the link with gold with the exception of the United States, which pegged the dollar to gold as early as 1919. In 1924, Sweden and Germany returned to the gold standard. More countries followed in 1925, such as England and Switzerland. On April 28, 1925, the Dutch government announced that it would return to the gold peg.

The return to the gold standard also called for a settlement of German reparations. The Germans were experiencing great difficulties with these payments and had fallen back on the printing press out of desperation, resulting in devastating hyperinflation. During the negotiations, an idea arose for a central office to streamline reparations. Out of this idea later grew the Bank of International Settlements (BIS).

DNB was involved in the establishment of the BIS and also bought shares, which enabled it to participate in the decision on the location of the institute to be established. The chances of Amsterdam as a business location were quite small from the start, as many German bankers were active in our capital and therefore the objectivity of the bank was at stake. Although Brussels tried to claim the institute, the bank settled in Basel. Because of the travel time, this was reason enough for DNB President Vissering to dread the monthly meetings. The expectations of the BIS were already low within DNB and President Vissering was ailing with his health.

The first building of the BIS (Source: ENCORE)

The first building of the BIS (Source: ENCORE)

When the gold standard came into effect, DNB made gold available for export to countries that had also introduced the standard. Because the Netherlands had actually built up too large a gold reserve during the First World War, part of the gold was sold in order to make the international distribution of gold fairer. This had no effect on the exchange rate of the guilder, as DNB received interest-bearing balances in other currencies in return.

Because exchange rates are stable under the gold standard, a transfer of gold before World War I really only took place when the price of a currency became overvalued. DNB was now able to determine the interest rate itself by managing the foreign exchange portfolio, as described in the book 'De Nederlandsche Bank', by Wim Vanthoor. If the bank sold gold, DNB received foreign currency and the exchange portfolio increased. As a result, interest rates fell. On the other hand, interest rates rose as the Bank's foreign exchange portfolio declined.

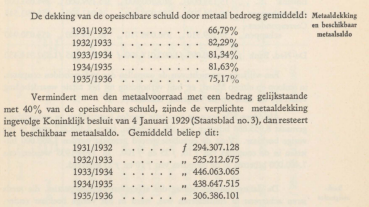

The bank's comfortable gold position was reason enough to raise the metal coverage of paper money back to 40 percent. The Bank had reduced the coverage to 20 percent during the war, as we described in an earlier article. Because the foreign foreign exchange portfolio also served as a hedge, the coverage of the paper money rose to more than 80 percent over the years, according to DNB's old annual report.

(Source: Annual Report Financial Year 1935/1936, page 41)

The gold standard didn't seem to work anymore after World War I. The British pound had returned to pre-war parity, making the currency highly overvalued. On the other hand, the French franc was greatly undervalued, leaving the balance of payments in a permanent surplus. However, because capital movements had also developed further, it was easier to compensate for balance-of-payments deficits.

A new reality had also emerged with regard to wages, in which wages were no longer reduced. Whereas a restrictive monetary policy previously required a fall in the price level, this became much more difficult after the war due to the so-called downward wage rigidity. This system was therefore less rigid than the pre-war system.

On top of that, the stock market crash in New York kicked off a severe depression. This crisis also led to problems in Europe and a banking crisis arose. The exchange rate of the British pound then came under pressure. In 1931, the Bank of England suspended the issuance of gold, causing the pound to fall at the same rate. The Netherlands tried in vain to get a guarantee from the British. The pound fell and that had major consequences for our country, as the Netherlands had deposited large amounts of money with the Bank of England. DNB's loss amounted to 29.9 million guilders. This loss had to be partly covered by the government.

The Netherlands did not finally leave the gold standard until 1936. In the years before, there had been a discussion about this decision. The aversion to devaluation as a means of countering deteriorating competitiveness was partly ethically motivated. Devaluation was seen as an act of bad faith and an artifice in the process of price formation. DNB President Trip called devaluation an inappropriate weapon, for which the Netherlands would be punished in the long run. Also, a large group of economists were still striving for a pure gold standard, in which world trade would flourish.

But attempts at such an initiative failed, giving strength to the argument for decoupling with gold. Also, by rejecting devaluation, the Netherlands had to rely on other and much more difficult ways to deal with the overvalued guilder. For example, the government could choose to introduce import tariffs and export subsidies across the board, but that was not an attractive option for an open economy.

The alternative was a policy of internal cost-cutting. Prices of products would become cheaper again. But as can be read in 'A Financial History of the Netherlands' It was not possible to bring prices down because this policy was accompanied by budget deficits and protectionist measures in the agricultural sector. The criticism of sticking to the gold standard had little impact. The Netherlands did not leave the gold peg until 1936, and that was because France and Switzerland also abandoned the peg, not because DNB president Trip and the government were convinced.

The Netherlands suffered a major loss due to the fall of the British pound. DNB's loss had been eliminated on the eve of the Second World War, but hopes of returning to a gold standard had vanished. In the Second World War, new challenges awaited. That's what the next piece in the series on monetary history is about.

Have a look at us YouTube channel

On behalf of Holland Gold, Paul Buitink and Joris Beemsterboer interview various economists and experts in the field of macroeconomics. The aim of the podcast is to provide the viewer with a better picture and guidance in an increasingly rapidly changing macroeconomic and monetary landscape. Click here to subscribe.