9.4

7.521 Reviews

English

EN

In the previous article in the series on the monetary history of the Netherlands, we described how the Netherlands was forced to switch to the Gold Standard despite its preference for the double standard. This period was known as La Belle Epoque; a period of flourishing world trade and political calm. With the outbreak of the First World War, this period was rudely disrupted. For four years, countries would fight each other in the trenches. Although the Netherlands remained neutral, the war had major consequences for the Netherlands. How did the Dutch Central Bank respond to this?

In the middle of the nineteenth century, there were still many areas in the Netherlands that were deprived of banking services. Banks were mainly located in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Twente (because of the textile industry in Enschede). After 1860, the banking industry grew enormously. For example, the Twentsche Bank From 1867 to 1890 its balance sheet total increased from 3.5 to 31.5 million guilders. The bank grew rapidly and also opened branches in Amsterdam and London. Later, the Twentsche Bank merged into a merger that resulted in the Algemene Bank Nederland (ABN) and later ABN-AMRO.

The Twentsche Bank in Enschede in 1920 (Source; Enschede in Postcards)

Lending only gained a foothold in other areas when the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) began to expand its branch network, which the bank was required to do by the Banking Act of the Netherlands .1863. DNB branches were established in several places in the country. As a result, the Dutch Central Bank acquired a national character. DNB's expansion also made it easier for local banks to develop. As a result, DNB was previously a Bankers' Bank. In the years before the First World War, these banks were increasingly able to finance their own lending. DNB therefore played a major role in the growth of the banking sector.

Nevertheless, the banking sector in the Netherlands was still lagging far behind the banking sector in neighbouring countries. For example, the share of banknotes in the monetary aggregate wasM1 still 64% in 1914. M1 is the aggregate consisting of banknotes and balances that can be demanded on demand. In Belgium and Germany, this percentage was just over 30 percent. Commercial banks therefore played a much larger role in the supply of money there than in the Netherlands, according to A financial history of The Netherlands.

After the assassination of the Crown Prince of Austria-Hungary, unrest grows in Europe. Countries are mobilizing their armies. Although the Netherlands wanted to maintain strict neutrality, men were also called up to do their military service. Things are going uneasy at the Amsterdam stock exchange. After stock exchanges elsewhere in Europe close, the Damrak also closes its doors.

The stock market closure prevented a total collapse of the stock market. There would be a vicious circle if the stock exchange remained open. Many investors wanted to get rid of the shares they owned, which had often been bought with borrowed money. However, these shares also acted as collateral for loans. As a result, additional collateral had to be deposited, but if this was not possible, part of the shares were sold.

After the stock exchange closed in August 1914, a support fund was set up to compensate for liquidity shortages. As it was expected that the number of banknotes issued by the fund would increase significantly, the funding ratio that had previously been40 percent reduced to 20 percent. Since DNB decided on the allocation of the resources from the support fund and the bank tried to place the loans with commercial banks, the cooperation between DNB and the banks also became increasingly close. As a result of this cooperation, DNB has increasingly become the central institution of the country.

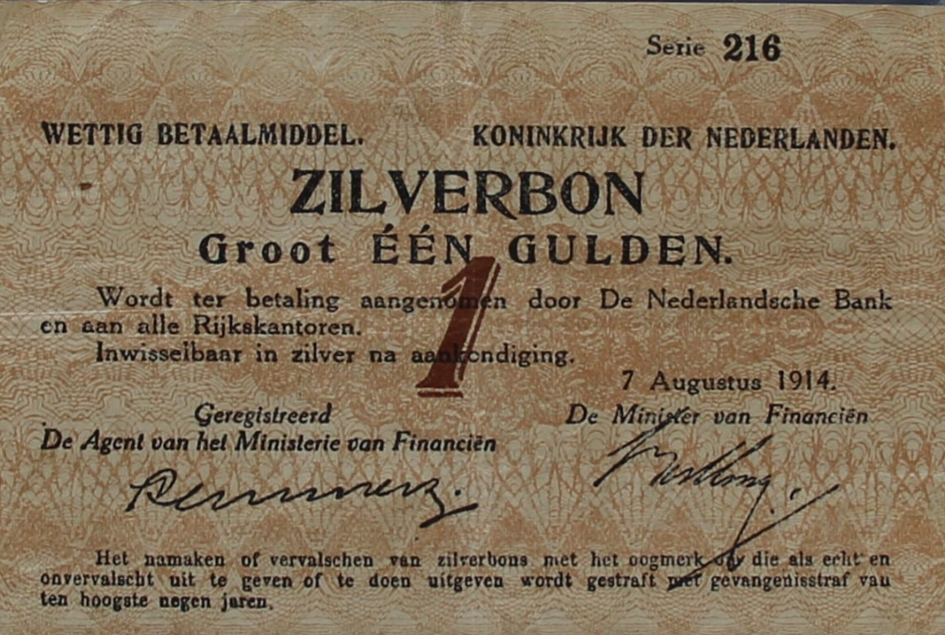

The announced mobilization caused panic among the population, causing a run on the Dutch Central Bank. On the one hand, there was a run on precious metals because the convertibility of banknotes was viewed with suspicion. On the other hand, the demand for these banknotes also increased sharply, as many products began to be hoarded as a result of the uncertainty. In order to provide enough banknotes, the silver voucher was introduced in denominations of one, two guilders, fifty and five guilders. These were issued by the Ministry of Finance.

Silver voucher issued in 1914 (Source: Frisianumismatica)

At the same time, the Netherlands followed the example of surrounding countries and suspended the gold standard with effect from 31 July 1914. At the same time, DNB banned the export of gold. Since other countries paid for Dutch products with gold and the Netherlands was attractive for foreign flight capital because of its neutral position, there was a large surplus on the balance of payments. The gold supply increased sharply during the war years. In 1913 the gold stock still amounted to 6 percent of the gross domestic product, in 1918 this had risen to 17.5 percent. This amounted to more than 700 million guilders in gold, as can be read in the book The Dutch Central Bank by Wim Vanthoor.

In his book, Wim Vanthoor also offers an overview of the so-called gold issue, a discussion about the large gold reserves of the Netherlands. There was a difference of opinion as to whether the influx of gold was desirable. For example, critics were afraid of inflation. There was a lot of gold in DNB's vaults. In addition, banknotes only had to be backed by precious metals for twenty percent, which gave the Bank a lot of room to provide credit. All that credit, according to critics, would trigger massive inflation. At the time, it was also questionable whether gold would regain the same status after the First World War as it did before the war. After all, countries had abandoned the gold standard en masse. If gold were to lose its monetary status, the Netherlands would probably suffer a large loss on gold.

DNB President Gerard Vissering disagreed with the criticism. According to Vissering, the Netherlands would only hinder trade with foreign countries if it no longer wanted to be paid in gold. According to the president, the Netherlands had to work hard to maintain gold, so that it would return in full glory as a currency anchor after the war. Vissering was not afraid of possible inflation, since in addition to a higher supply of money, a much greater demand for money had arisen. In addition, part of the money was not spent, but was kept under a mattress or in an old sock. As a result, money was in circulation in theory, but it should not actually be counted as circulating money.

As a result, DNB became increasingly important in the years of the First World War. It is very interesting to read about the monetary discussions of the time. DNB would continue to play an increasingly important role in the years after the war during crises and turmoil. We will describe this in more detail in the following sections. In this way, DNB increasingly became the central bank it is today.

![]() Have a look at us YouTube channel

Have a look at us YouTube channel

On behalf of Holland Gold, Paul Buitink and Joris Beemsterboer interview various economists and experts in the field of macroeconomics. The aim of the podcast is to provide the viewer with a better picture and guidance in an increasingly rapidly changing macroeconomic and monetary landscape. Click here to subscribe.