9.4

7.521 Reviews

English

EN

Han de Jong was the chief economist of ABN Amro for many years, but he started his career at a secondary school as an economics teacher. De Jong can now be heard regularly on BNR Nieuwsradio and writes weekly columns and commentaries on his website Crystalcleareconomics.nl. We talked to the former chief economist about inflation, monetary policy and the business climate in the Netherlands. What is De Jong's view on these subjects?

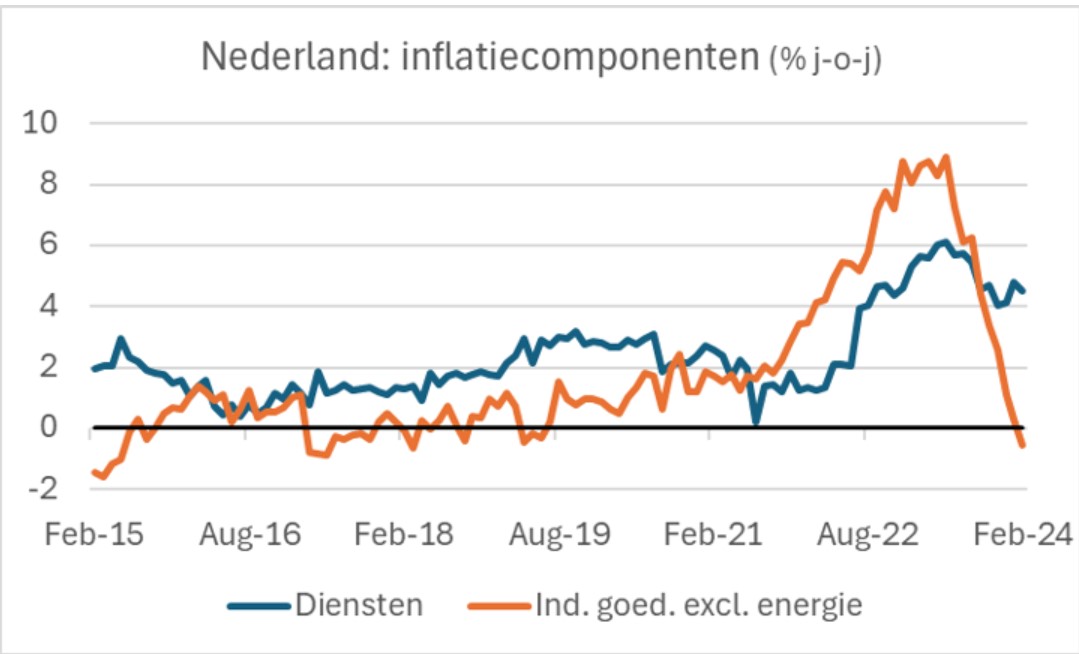

In his columns, De Jong discusses the inflation figures on a monthly basis. Inflation has fallen sharply in recent months. In February, the price increase was 2,8 percent, while in September 2022 CBS was still 17,1 percent. That is of course a good development, but De Jong is still cautious: 'There are two things that I am still worried about. First, the underlying dynamics are much more turbulent than before the pandemic. The inflation rate refers to the increase in prices across the board, but there are large differences between different components. Second, the rise in prices in the services sector is largely caused by the increase in labour costs. As a result, inflation in that sector is very persistent."

Inflation is already a lot lower than in 2022, but services are still rising sharply in price. (Source: Crystalcleareconomics)

Inflation is already a lot lower than in 2022, but services are still rising sharply in price. (Source: Crystalcleareconomics)

Due to the tight labour market, it is quite possible that inflation will be higher than the policy target of two percent for some time to come. The effect of previous interest rate hikes is also not yet fully visible, as monetary policy usually works with a lag of a year and a half. This makes it difficult for the central bank to decide when to cut interest rates. On the one hand, inflation is still too high, but on the other hand, there are also Economists who would like to see an interest rate cut to stimulate the economy.

According to De Jong, due to the delayed effect of the policy, the ECB does not have to wait for inflation to arrive exactly at the policy target. 'If the ECB waits too long to ease, the central bank may keep interest rates too high for too long. At some point, as a central bank, you have to make the decision to lower interest rates. If I were in charge, I would wait a little longer, but it seems as if the ECB has already decided that interest rates will be lowered in June," says the economist.

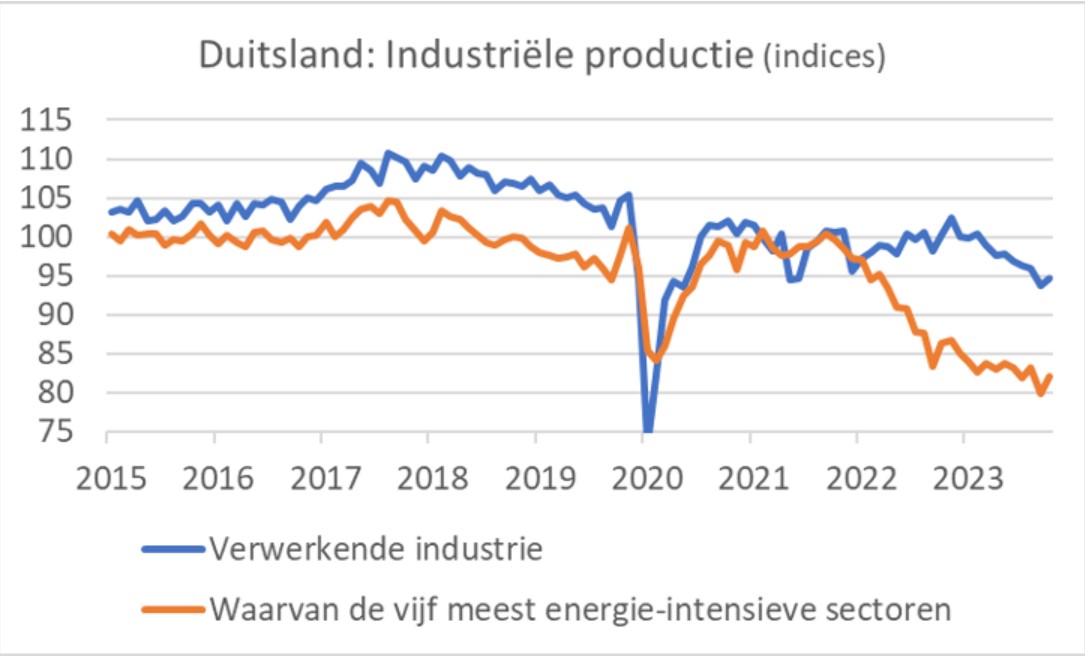

De Jong has repeatedly expressed his concerns about German industry, but does not think an interest rate cut is justified to pull the sector out of the doldrums: 'High energy prices in particular are problematic for German industry. The central bank's main task is to maintain price stability and, if necessary, this is accompanied by a recession. The problems in German industry do not seem to me to be a reason to cut interest rates very quickly."

Production in Germany has fallen sharply since high energy prices. (Source: Cystalcleareconomics)

Production in Germany has fallen sharply since high energy prices. (Source: Cystalcleareconomics)

The pessimism among our eastern neighbours does not immediately mean a comparable development in our country. This is because the structure of the Dutch economy differs from the German one. For example, Germany has a large automotive industry and other heavy industries, such as the chemical industry. The Netherlands has this to a much lesser extent, but focuses more on other sectors such as IT. As a result, the outlook for the Netherlands is slightly more positive.

Nevertheless, the trend for Europe is not very optimistic. 'We are making it very difficult for ourselves in a number of areas. We are struggling with very high energy prices and would also like to be at the forefront of the energy transition. At the same time, there is a huge regulation coming from Brussels and that all eats up capacity. As a result, labor productivity in America is increasing, while productivity in Europe is decreasing. That is a worrying development,' says De Jong.

In recent weeks, the Dutch business climate has been surrounded by enormous publicity after ASML expressed doubts about future investments in the Netherlands. Han de Jong is also worried: 'Last week, the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) showed in the annual report There are a number of rankings that showed that the Netherlands is doing very well internationally, but I think that in recent years a very negative atmosphere has arisen around market forces, entrepreneurship and the business community.'

Compared to 2008, fewer Dutch companies in the list of the world's largest companies. Some companies simply did not grow fast enough and other companies left the Netherlands, such as Shell and Unilever. From a macroeconomic point of view, a country does not notice much of the departure of a head office, but high-quality employment does disappear. 'And that's definitely a problem. After all, everyone benefits from jobs with high labour productivity. I often illustrate this with the example of two hairdressers, one in Kenya and one in the Netherlands. Both do the same job, but because the Dutch hairdresser cuts customers with a high income, a higher price can also be asked. So hairdressers also benefit from high-quality employment,' says De Jong.

The Netherlands would therefore do well to keep the business climate favourable. In addition, there are many small things that would make our country more attractive, such as maintaining the expat scheme, but it must also be fiscally attractive to work in the Netherlands. According to De Jong, it would not lead to problems if the national debt increased. 'The Dutch national debt is well below 60 percent and if you include the deferred tax claim on the pension money, the national debt is even smaller. But if the national debt rises, it also means that the budget deficit increases, and that is against European fiscal rules. We can no longer maintain that other countries should do something about the high national debt,' says De Jong.

Recently we discussed Lex Hoogduin and Kees de Kort Holland Gold the ECB's approach to climate policy. De Jong also has his doubts about the ECB's policy: 'I think the ECB is completely politicising. They argue that it is within the mandate, since the ECB should also support the EU's economic policy, but then the ECB would have to do so in other areas as well. Why is the ECB not working on digitalisation? Or something else, or all at once?', De Jong wonders.

Moreover, you could argue that climate policy is not in line with the ECB's objective, because according to De Jong it tends to increase costs. The U.S. central bank has indicated that climate policy does not fall within the mandate of the central bank and that climate policy extends over a much longer period of time than the central bank's policy. 'I don't have a good word to say about what the ECB is doing,' says Han de Jong.