9.3

8.064 reviews

English

EN

This article has been automatically translated from Dutch. Click here to see the orginal article including all links to sources.

This week again brought several important developments. Here’s an update on four key topics we’re closely monitoring: the decline in Dutch industrial competitiveness, the EU’s stance on Russian gas, France’s push for joint European debt, and the continued gold purchases by central banks.

The Dutch industry remains burdened by high energy costs and additional levies. A resumption of Russian gas imports — which might have eased the pressure — now appears firmly off the table. Meanwhile, France is attempting to shift its debt burden onto the Dutch taxpayer. And central banks around the world are continuing to buy gold, as confirmed by a new World Gold Council survey. Read on for our full analysis!

Chemical companies provide essential raw materials for countless sectors. Yet this seems to be lost on some Dutch politicians. Another chemical plant is shutting down in Rotterdam. Back in March, we already reported on the closures of LyondellBasell and Tronox facilities. Now it's Westlake's turn. The American company’s factory in Pernis, which employs 230 people, produces epoxy and synthetic resin.

According to De Telegraaf, the Dutch chemical sector is now facing a domino effect of decline. Last month, Finnish firm UPM cancelled plans to build a biofuel plant, citing excessive costs. Dutch industry continues to struggle with relatively high energy prices and a CO₂ levy that makes domestic production less competitive. Nitrogen restrictions and electricity grid congestion aren’t helping either.

Electricity costs for businesses in the Netherlands are up to three times higher than in France. On top of the EU-wide CO₂ pricing mechanism, the Netherlands has imposed an additional national levy. By 2035, Dutch companies are expected to pay about €75 more per tonne of CO₂ emitted than their European counterparts. “It is crucial that this uniquely Dutch tax is scrapped as soon as possible so we can once again compete fairly with surrounding countries,” said Frans Everts, CEO of Shell Netherlands.

Despite industry protests, caretaker Deputy Prime Minister Sophie Hermans (VVD) reportedly insisted on keeping the extra levy. According to De Telegraaf, she personally ensured the measure remained in place.

“That’s absurd,” economist Lex Hoogduin wrote on X. On Tuesday, the European Parliament in Strasbourg presented a proposal for a permanent import ban on Russian gas — one that would remain in force even after the war in Ukraine ends. The import of Russian gas must end by 2027 at the latest.

“This is an import ban we’re introducing because Russia has blackmailed us and cannot be trusted. Even if a peace deal is reached, the ban stays,” said EU Energy Commissioner Dan Jørgensen, according to Het Financieele Dagblad. He also claimed that the move should not be considered a sanction. This is curious, given the Financial Times cited him as saying: “It would be extremely unwise to resume gas imports, as it would once again fill Putin’s war chest.”

Ursula von der Leyen (source: Raul Mee/EU2017EE)

Back in May, we already reported that Commission President Ursula von der Leyen wants to rule out any return to Russian energy. At that time, opposition had already emerged from German industry, Hungary, and Slovakia — all heavily reliant on Russian gas. Austria has now also joined the opposition. Brussels “must retain the ability to reassess the situation once the war is over,” the Austrian energy ministry told the Financial Times.

Austria was long dependent on Russian gas, importing around 80% of its supply from Russia prior to the war. Italy — the EU’s largest importer of Russian gas last year — has reportedly also floated the idea, behind closed doors, of resuming imports post-war.

This resistance may explain the contradictions in Jørgensen’s remarks. True sanctions require unanimity among EU member states, and Hungary and Slovakia have already said they would veto such measures. That’s why the current proposal is framed not as a sanction, but as a trade measure — which only requires a qualified majority to pass.

According to the Financial Times, France has urged other EU member states to take new steps to boost the euro’s status as a global reserve currency. Paris argues that investors are seeking a safe alternative to U.S. Treasuries, and the EU should issue more joint debt to meet this demand.

French ECB President Christine Lagarde — perhaps not coincidentally — published an op-ed this week in the FT titled: “This is Europe’s global euro moment.” She wrote that the euro could gain ground against the U.S. dollar, and stressed the importance of a broad supply of safe assets for any international currency. In doing so, she effectively endorsed France’s push for more common debt issuance. ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane echoed this sentiment, citing a shortage of safe assets in Europe and pointing to a paper by renowned French economist Olivier Blanchard.

Christine Lagarde (source: Martin Lamberts/European Central Bank)

The EU is already struggling to repay the nearly €800 billion in joint COVID recovery debt. According to the European Commission, starting in 2028 about €30 billion per year will be needed for repayments — unless new refinancing is arranged. France, however, argues that issuing more debt could improve market liquidity and attract investors.

Such joint borrowing would require approval from countries like Germany and the Netherlands — both of which would bear a larger share of the financial burden. Unsurprisingly, this has led to the question: Will Dutch taxpayers be forced to foot the bill for French debt?

France’s lobbying push is no accident. Government spending now accounts for 57% of France’s economy — the highest in the EU. Public debt is already very high and continues to rise due to persistent budget deficits. Structural reform is politically difficult in France, where around 60% of the electorate depends on public funds.

Taxes are already among the highest in Europe, and spending cuts seem politically impossible. We wrote back in April about France’s “debt paralysis.” It’s hardly surprising that Paris is now searching for an escape route — and hopes to find one at the expense of Dutch and German taxpayers. The key question is: Will we go along with it? Let’s hope this becomes a major election issue.

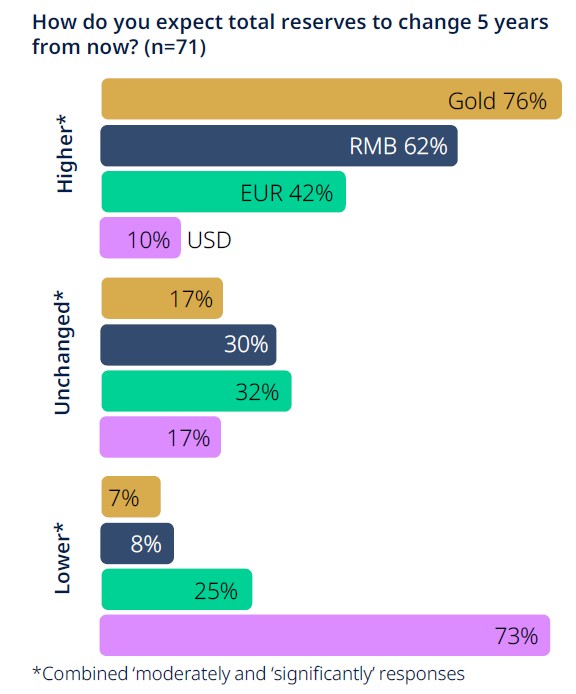

Christine Lagarde may hope the euro benefits from a shifting world order and a weakening dollar — but for now, gold seems to be the main winner. According to a new survey by the World Gold Council (WGC), a large majority of the 71 central banks surveyed expect their gold reserves to increase over the next five years.

Resultaten peiling centrale banken over reserves (bron: World Gold Council)

Against a backdrop of geopolitical tensions, the threat of sanctions, and growing doubts about the dollar’s reserve status, central banks have been buying gold at record pace. Gold has now overtaken the euro as the world’s second most important reserve asset, behind the dollar. As Shaokai Fan of the WGC told the Financial Times: “The sentiment is exceptionally strong. Central banks are increasingly confident not only in their own gold buying, but also in the likelihood that others will continue to buy.”

To be continued!