9.3

8.064 reviews

English

EN

This article has been automatically translated from Dutch. Click here to see the orginal article including all links to sources.

There’s a deficit, but no one is cutting spending. So the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer is trying to close the gap with tax hikes. But it’s backfiring: higher rates are yielding lower revenues. And the eurozone? The picture is bleak there too. Germany is shrinking, the Netherlands is stagnating, and only Spain still shows signs of life. Also in this week’s update: gold demand remains strong, despite record prices. We dive into the latest report from the World Gold Council.

The UK government, led by Labour Prime Minister Keir Starmer, is scrambling for additional revenue. With public spending out of control, the government is trying to boost tax receipts. But in practice, higher taxes don’t always mean higher revenues—a textbook example of the Laffer curve.

The attempt to extract more revenue from capital gains tax has had the opposite effect. This tax is levied on profits from the sale of assets like businesses, second homes, or shares. Revenues from capital gains tax dropped sharply after the tax-free threshold was slashed from £12,300 to £6,000. The result? Revenues fell by 18 percent to £12.1 billion in the 2023–24 fiscal year.

Rachel Reeves (Source: House of Commons)

Chancellor Rachel Reeves isn’t done yet. In October, the tax rate on capital gains was raised to a band of 18 to 32 percent (up from 10 to 28 percent). At the same time, the tax-free allowance was halved again, to just £3,000 per year. According to preliminary estimates by the UK tax authority, revenues from this tax are expected to drop by another 10 percent in the 2024–25 fiscal year. Some Brits rushed to realize their gains before the changes. Others are holding onto their paper gains and waiting it out.

Reeves now needs to close a budget gap of £20 to £30 billion, as earlier planned cuts to public spending have been shelved. Her options are limited by Labour’s pledge not to raise income tax, VAT, or National Insurance contributions for “working people.” So she’s turning to other taxes—but this could backfire, as people adjust their behavior to avoid higher tax burdens. And that goes beyond delaying gains on second homes or equities.

Since early 2024, thousands of wealthy foreigners have turned their backs on the UK following the abolition of a centuries-old tax break, which had allowed so-called “non-doms” to avoid UK taxes on foreign income for up to 15 years. The Adam Smith Institute published a report warning that the country could lose up to £111 billion in the next decade, along with over 40,000 jobs.

You can’t keep raising taxes indefinitely and expect prosperity to hold up. Sooner or later, people change their behavior. That’s why governments must get spending under control. It’s not surprising, then, that the ideas of Javier Milei have now made their way into the UK debate. We wrote about it last week.

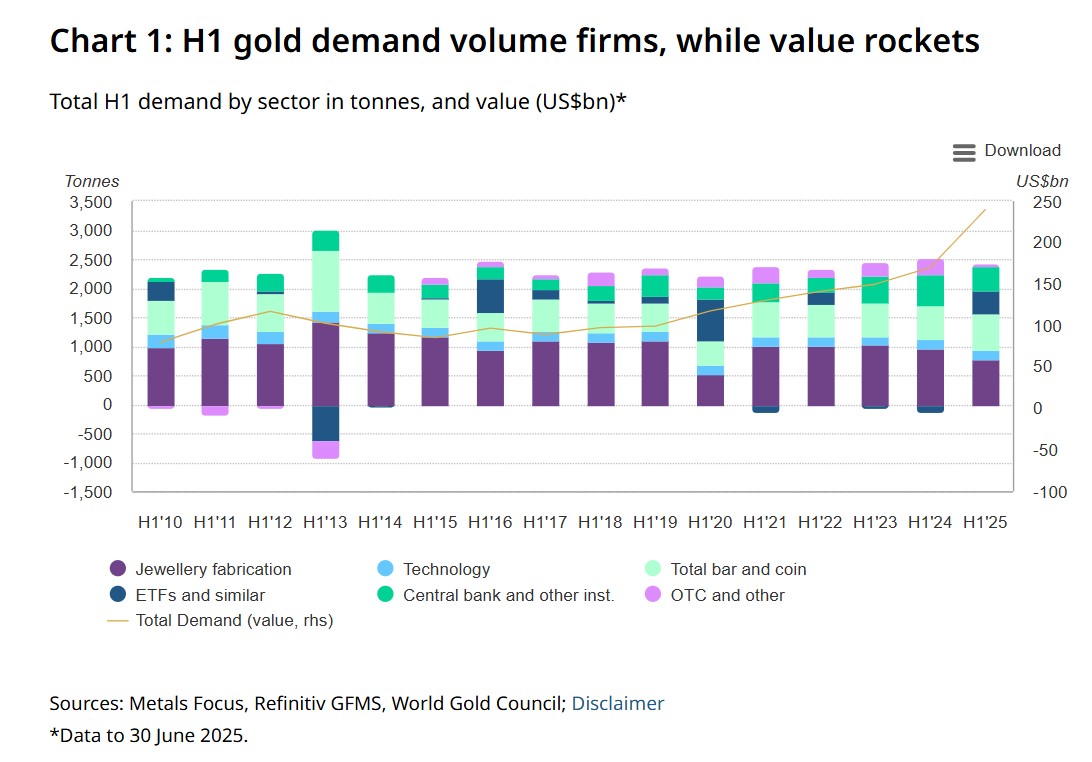

According to the latest quarterly report from the World Gold Council (WGC), demand for gold remains robust, even as prices hit record highs. Compared to a year earlier, gold demand rose 3 percent in the second quarter to 1,249 tonnes. In value terms, the increase was even more striking: up 45 percent to $132 billion.

Gold demand in H1 since 2010 (source: World Gold Council)

Central banks remained a key pillar of global gold demand, adding 166 tonnes to their official reserves in Q2. Still, the pace of buying was slower than before—marking the lowest level since 2022, though still 41% above the 2010–2021 quarterly average. The WGC expects the long-term trend to continue, in which central banks shift their allocation from US assets to gold. This expectation is backed by an extensive survey of central bankers, which we covered earlier.

For the second consecutive quarter, gold-backed ETFs saw strong inflows, contributing significantly to total demand. Demand for gold bars and coins also surged, reaching its highest level since 2013. According to the WGC, this reflects uncertainty around trade wars and geopolitical tensions. Investors are seeking safe havens and are being drawn to gold not just by fear, but also by its rising price.

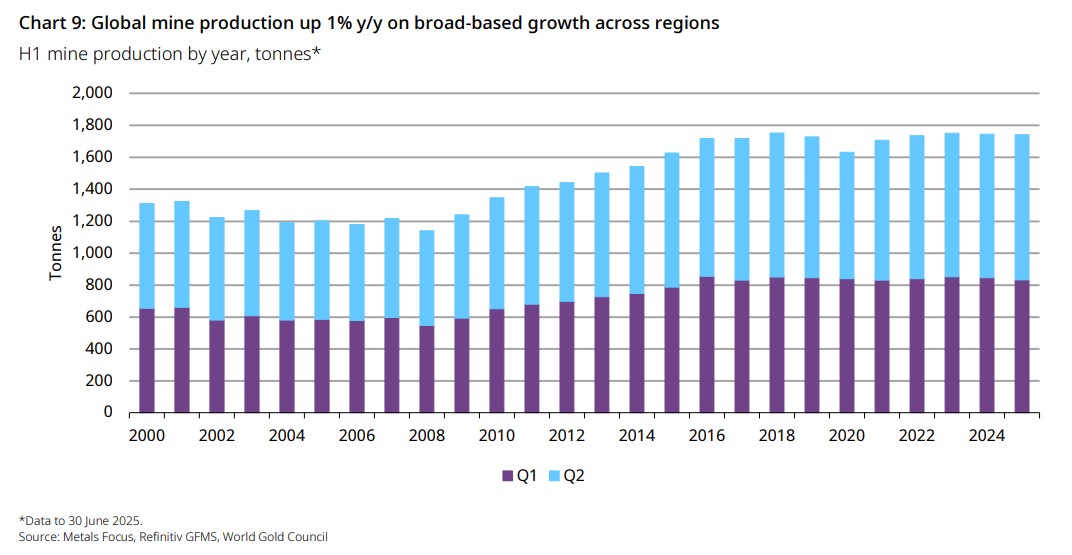

Gold production in H1 since 2010 (source: World Gold Council)

Gold mine production rose just over 1 percent in Q2 compared to a year earlier, to 909 tonnes. Recycled gold supply also increased—up 4 percent year-over-year to 347 tonnes. Total gold supply rose by 3 percent overall.

The WGC expects both gold buying and prices to remain elevated for the time being. “To be truly bearish on gold, you’d have to believe in sudden reasonableness and cooperation among the world’s major geopolitical leaders. And the world seems far too polarized for that,” said John Reade, senior market analyst at the WGC, in the Financial Times.

The WGC recently published an extensive forecast for gold prices in the second half of 2025, based on three scenarios. Read it here!

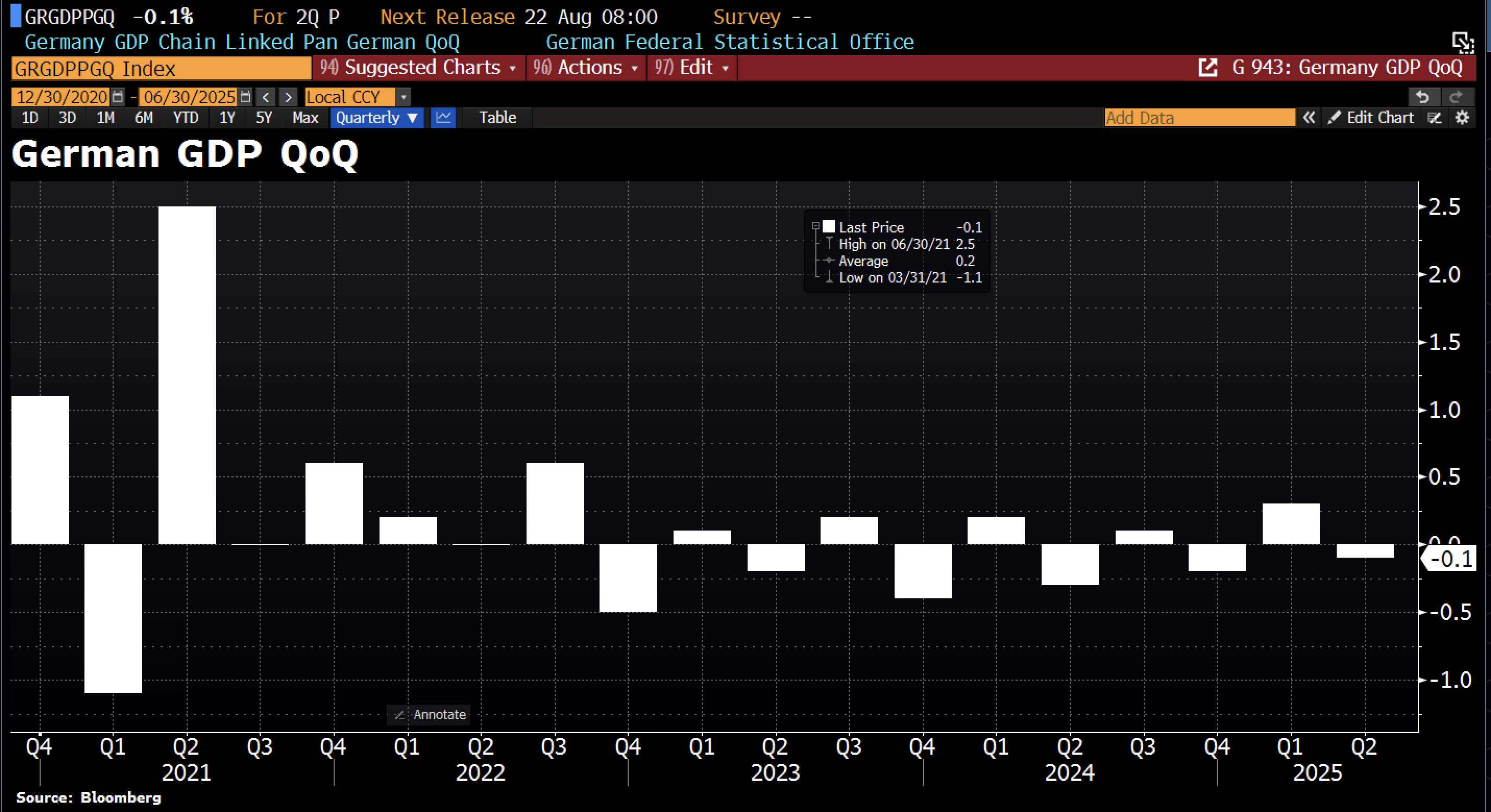

It was a week full of economic data. On Wednesday, preliminary figures from the German statistics office Destatis showed that Germany’s economy shrank slightly in Q2 2025—by 0.1 percent compared to the previous quarter. Germany has been stagnating for some time now.

German GDP trend (source: Holger Zschaepitz)

The old growth model—cheap Russian gas, an undervalued currency, and strong exports to China—is obsolete. But a new path toward sustainable growth has yet to be found. And the impact of the recent Trump–Von der Leyen trade deal still lies ahead. This week, Germany’s economics minister admitted that the welfare state is under pressure and that a tipping point is drawing near. In our podcast with economist Han de Jong, we discussed Germany’s challenges.

The Dutch economy is still growing, but just barely. According to Statistics Netherlands (CBS), GDP rose by only 0.1% in Q2 compared to the previous quarter. Growth has been weakening for five straight quarters and has nearly come to a standstill. “The economy is slowly running out of steam,” CBS chief economist Peter Hein van Mulligen told the Dutch broadcaster NOS. Household consumption fell by 0.4 percent, while government spending increased by 0.8 percent. So the limited growth we saw last quarter was largely driven by public expenditure.

Eurostat also released new figures on the eurozone economy on Wednesday. Like the Netherlands, the eurozone as a whole grew by just 0.1 percent in Q2. The previous quarter had seen stronger growth of 0.6 percent, largely driven by businesses front-loading purchases to avoid new import tariffs. Still, there were some bright spots. France performed better than expected, growing 0.3 percent in Q2. Spain did even better, with 0.7 percent growth—the highest in the eurozone.

ECB President Christine Lagarde told journalists last week that the eurozone economy had performed slightly better than expected so far this year. “We’re in a good position,” said Lagarde. Of course, it all depends on what you’re comparing yourself to—because for now, European policymakers can only dream of growth rates like those seen in Argentina.